By Nina Heyn – Your Culture Scout

Unless you are writing a script for a TV show, writing is a decidedly solitary occupation (you can hardly write a novel “together”). Painting is a bit more conducive to communal activity and many artist communities sprung up throughout the 19th century. Once some artists discovered a particularly picturesque and hopefully not too expensive area, they would flock there to at least hang out together in the evening, if not exactly paint side by side. Some famous painting communities emerged, and many of them have remained artists’ colonies to this day.

Barbizon

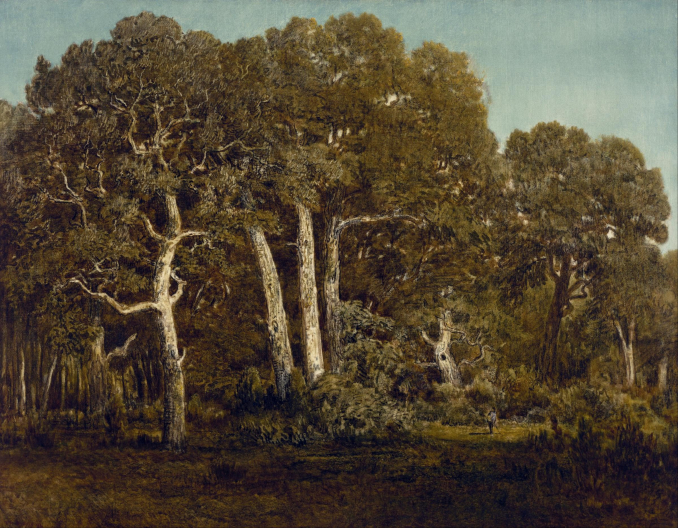

Realistic landscape painting became popular among French artists after they were exposed to the nature paintings of John Constable, whose large 1824 exhibition was a Paris sensation. At the time, younger French painters were also reacting to the pedanticism and mythological themes of the academic style that then dominated the art scene. Painters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot were looking for places that would provide unspoiled views of trees and land to create realistic renditions of nature. One of the earliest spots for an artists’ community was Barbizon, a small place about 40 miles (70 km) south of Paris at the edge of the scenic Forest of Fontainebleau. When Corot arrived in Barbizon in 1829, not only did he find the nature he was seeking, but he was eventually followed by many other Parisian painters. This small, stone-walled village embraced hordes of landscape artists, who found cheap lodging in local inns, evening entertainment and good food in local eateries, and the companionship and feedback of fellow painters. To this day, the walls of the old Auberge Ganne (the inn that now houses the Departmental Museum of the Barbizon School) are covered with drawings and decorations left there by visiting painters.

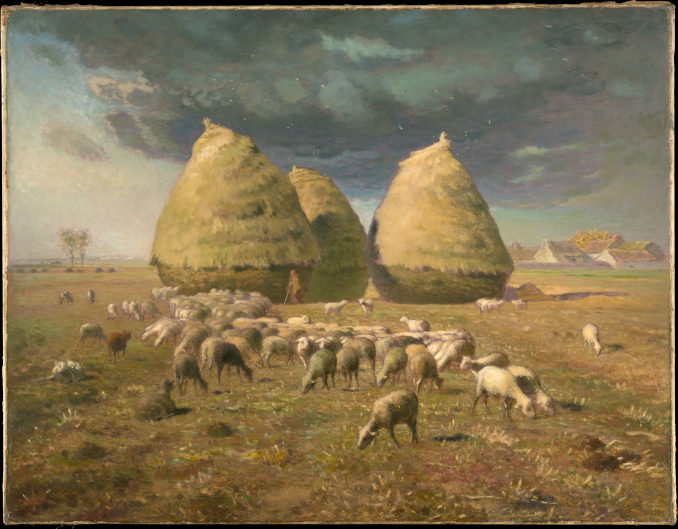

Two of the artists who are most associated with Barbizon (where they painted, suffered numerous health and life difficulties, and eventually died) are the naturalists Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet. Their strong association with this place and the generations of artists that their presence attracted every summer are responsible for the “School of Barbizon” name being given to the whole movement in nature painting, even if that name was not actually forged until 1891 by English art critic David Croal Thompson. It wasn’t even a “school” in the sense of one artist teaching another—but it described well all the artists who were inspired by Fontainebleau’s landscape, who wanted to paint differently than the academics, and who wanted to spend time together in Barbizon.

Rousseau, a self-taught artist who struggled all his life for proper recognition and who was plagued by ill health, started visiting Barbizon beginning in 1833. He finally settled there year-round in 1849—the year when Millet started coming regularly to Barbizon. Millet came to escape an epidemic of cholera, moving south to Barbizon with his wife and nine children. The two artists became lifelong friends. By the mid-1800s, Barbizon became a popular artist colony to be visited by anybody who wanted to paint outdoors. The invention of oil paints in tubes in 1841 made these plein-air activities much easier. Meanwhile, landscape art gained popularity and stature in the ranking of genres appreciated by both academicians and the public. Baudelaire wrote about another Barbizonian, the romantic landscape artist Charles Daubigny, that he “includes in the scenery all the nature and nothing but nature.”

Rousseau, Millet, and especially Daubigny influenced the next generation of painters who were interested in recording nature “as is” and who began paying visits to this art colony—the Impressionists. The very long list of artists who visited Barbizon at least once includes most of the 19th-century grand Impressionist figures—Courbet, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Seurat, and Sisley.

Barbizonians went in search of a France that was fast disappearing. The same urbanization and technological changes that made Paris the most modernized and progressive city in the world, made the world of gentle streams, pristine forests, and villages teeming with life something of a hard-to-catch past. Writers would evoke it in historical novels and romances set in a bucolic countryside, while artists tried to capture it in landscapes that paid homage to the English landscapes created a few decades earlier by Constable and other Romantics. But this bucolic world was becoming harder and harder to find near big cities, so the next generation of artists went to the Normandy coast in search of the unspoiled land.

Pont-Aven

The most famous of French artists’ colonies, the village of Pont-Aven on the Normandy coast, was discovered by an American artist named Henry Bacon. In 1864, Bacon made an accidental stop at the village and fell in love with its views and the exotic costumes of local women. After he started spreading his enthusiasm among his Anglo-Saxon friends, another American artist named Robert Wylie, who settled in Pont-Aven, soon persuaded other young American painters like Mary Cassatt and Thomas Eakins to visit. Within 10 years, the village had become a gathering place for painters. Even the master of historic and oriental tableaux, Jean-Louis Gerôme, who taught at the Fine Arts Academy in Paris, encouraged his students to visit the place.

By 1886, the village, crammed with painters and tourists alike, got one more artistic visitor: Paul Gauguin. A few years earlier, Gauguin had failed to be a stockbroker. He then tried living with his wife and their five children in her native Copenhagen, but he ended up abandoning them there and embarking on a new career as a full-time artist. His arrival at the tiny village of Pont-Aven would mark a milestone in the history of art. He was looking for an exotic place (and a remote place in Normandy populated by peasants in colorful costumes would be as exotic as possible for a Parisian), but what he also found was his own style. At Pont-Aven, Gauguin created his first amazing, stylistically different, and complex canvases and launched what was later dubbed the “School of Pont-Aven,” which included several artists active in that place between 1886-1894.

For eight years, Gauguin’s base in the village was an inn called Pension Gloanec, which provided cheap but plentiful meals and a perfect place for artistic gatherings. Painting together became a literal description in the case of a picture, ironically named School of Hotel Gloanec, that was painted by two Pont-Aven artists, Fernand Quignon and Hermanus-Franciscus Van den Anker. The oil panel below may be artistically mediocre, but it shows a view that must have been typical in the area at the time: a few easels are set up in a row on the beach for painters to work while vacationers watch.

In 1888, a budding 20-year-old artist named Émile Bernard arrived at Pont-Aven, where he met Gauguin and started to paint together with him in the style that is now called “synthetism” (flat surfaces, simplified shapes, bright palette). Bernard’s canvas, Breton Women Praying, is a good example of how close his art was to Gauguin’s at that time.

This artistic friendship did not last long because Bernard felt that he was not given sufficient credit for co-creating the new style. Three years later, Bernard and Gauguin parted ways. Bernard is now co-credited with the invention of “synthetism” (and another style called “cloissonnism”), but his later paintings document how much and how often he also emulated other styles (you can find echoes of van Gogh, Seurat, and Cézanne in his canvases). His works demonstrate his facility in absorbing styles and his great sensitivity to color, but it is a bit debatable how much Gauguin was actually indebted to the young Bernard. In any case, what is not up for debate is that Pont-Aven was a crucible for many amazing canvases created by Gauguin, Bernard, Charles Laval, Paul Sérusier, and others in the late 1800s.

St. Ives

St. Ives is a beach community that overlooks the blue waters of a bay in the southwestern corner of England. The popularity of this small port as an art colony started around 1870, when Cornwall’s coast was discovered as a chic holiday destination, easily reachable by newly built railways. It was the time when the very idea of “summer holidays” stopped being just a privilege of the rich and took off among the middle class. Painters such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Walter Sickert explored picturesque St. Ives as early as 1884, and within a few years it became a colony attracting many marine artists.

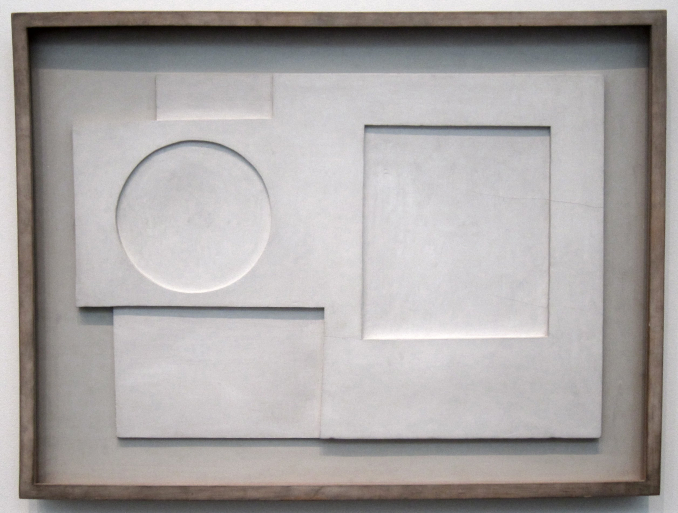

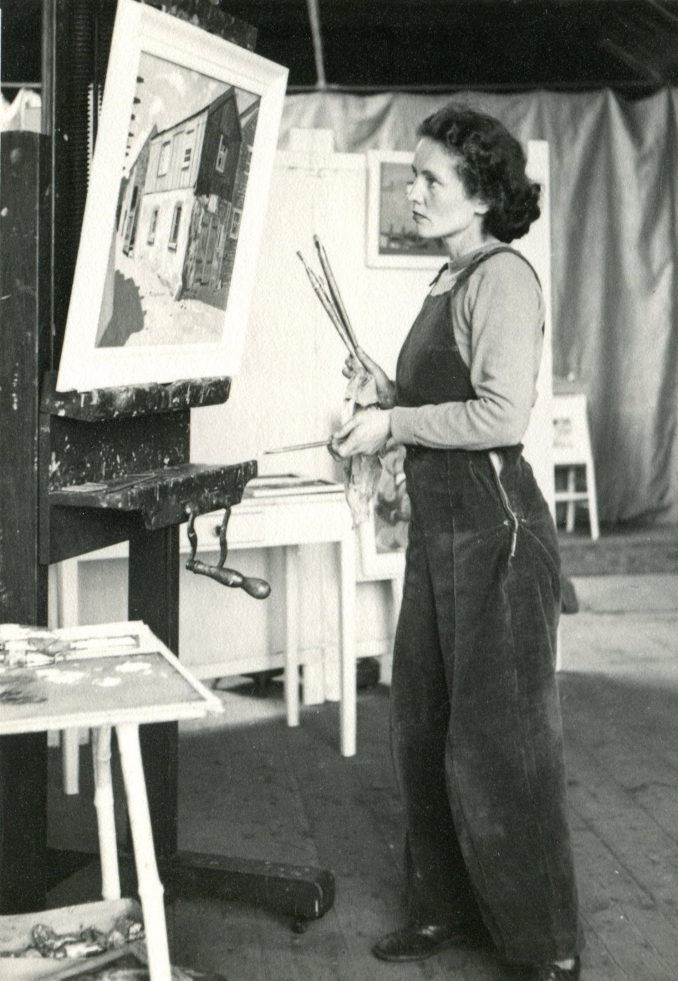

It was, however, the second generation of artists who made St. Ives famous as the largest art gathering place in the UK outside London. Sculptor Barbara Hepworth and abstract painter Ben Nicholson were both married to other people when they met in 1931, but within a short few years, they left their respective partners, became parents to triplets, and moved permanently to St. Ives, settling there just before the start of WWII. When London started being bombed, more artists began escaping to this remote village. Hepworth and Nicholson became the leaders of an artists’ community, including taking under their wing some refugees, such as the Bauhaus sculpture artist Naum Gabo.

Nicholson was an abstract painter whose 1930s works were pristinely monochromatic, strongly influenced by Mondrian, who abhorred both nature and the color green. Arriving in St. Ives changed all that. Nicholson started painting in colors, inspired by Cornwall’s greenery, sea, and skies. Colorful pictures, whether abstract or landscapes, were also easier to market, and Nicholson, by then the father of six kids from two marriages, needed to be more of a commercial success. The move to St. Ives marked the beginning of an explosion of Hepworth’s creative juices as well, with the place proving to be an ultimate source of inspiration for her.

While Hepworth and Nicholson were the indisputable leaders of the colony, other artists—especially St. Ives native Peter Lanyon and a bold abstractionist named Wilhelmina Barns-Graham—flourished in the lively 1940s art scene. English modernism thrived at St. Ives for about 10 to 15 years, thanks to the wartime arrivals and the light and beauty of the Cornish coast.

Other Art Colonies

Art colonies have not been limited to France and England. In Scandinavia, modernist painters gathered at the beaches of Skagen. In the Netherlands of the 1920s, painters worked together in the seaside town of Bergen, while during the same period in Poland, artists would paint at the country estate of Wiśniowa.

The trend of artists gathering in one location also crossed the Atlantic. At the start of the 20th century, there were some famous painting places in America as well. The first art colony was established in 1900 by Florence Griswold, who needed income to keep her family house and estate going. Her house in Old Lyme, Connecticut became a gathering place for many decades of artistic plein-airs. By the 1940s, other places also became popular art colonies. Provincetown, Massachusetts—the location that has the honor of being the longest continuously operating art colony in the U.S.—was associated with abstractionists Robert Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler. Sedona, a striking town nestled among the red rocks of Arizona, regarded by Native Americans as sacred, started to draw creative types after the surrealists Max Ernst and Deborah Tanning settled there after WWII. Ernst created his masterpiece sculpture Capricorn while living in Sedona.

People of similar interests tend to flock together even without any art involved. For artists and writers, however, this impulse seems to be an even more attractive way of sharing interests and inspiration. The communal spirit blends well with individual expression in art colonies. There are now hundreds of well-known artistic centers all over the world.